You can't plan things like this.

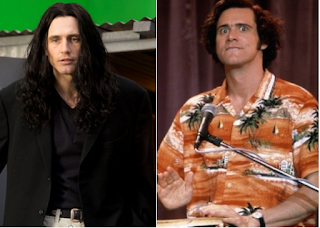

You can't plan things like this.The last two movies I saw -- because one was released on Thursday night, and because the other had been available for a few weeks on Netflix and was really starting to itch at my viewing desires -- were The Disaster Artist and Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond - Featuring a Very Special, Contractually Obligated Mention of Tony Clifton. (And that's the last time in this piece I will write out the full title, I promise you.)

Both films happen to be a behind-the-scenes look at the filming of a movie whose production was affected -- some might say poisoned -- by the antics of a highly eccentric personality. In one, the guy couldn't help doing it -- he was just playing himself, as he always had. In the other, one highly eccentric personality was channeling another highly eccentric personality, doing it purposefully in pursuit of what he perceived to be some very specific brand of the comedic sublime.

Both films are funny, instructive examinations of these particular minds, and I enjoyed both quite a bit, though stopped short of loving either.

I came closer to loving The Disaster Artist. Not only does James Franco nail Tommy Wiseau and explore in a more serious manner the things that have been the comedic objects of much of his work (latent homosexuality among them), but the film has a ton of heart. As much as it considers Wiseau an oddball and even leans into that, it also considers his optimism and can-do spirit the perfect antidote to Hollywood cynicism. The Room was a singularly disastrous film but it was also the result of a type of purity of impulse that we usually do not see in the movies.

Jim & Andy is a fascinating document, to be sure, but I'm not sure it gets much beyond that (pun not intended). It considers how far Jim Carrey went in trying to channel dada comic Andy Kaufman, not only staying in character as Kaufman even after Milos Forman called "cut!" on Man on the Moon, but also playing Kaufman's alter ego, Tony Clifton, such that the actual "Jim Carrey" was almost never present. A cameraman shot all this behind the scenes footage and it has been sitting in the vaults for 20 years. Carrey gives modern-day interviews recalling his thinking at the time, impressive beard and all.

Both films provide a very interesting examination of what happens when the cameras aren't rolling. To be sure, they are not the first films to do this -- there's a whole interesting subgenre of films which show us what actually happened on the sets of movies we love. Few of them are quite so focused on the way a single man can hijack the production, while also shaping it into the movie we love as a result.

For those who love The Room, they only love it because Wiseau was unfailingly who he was and would not listen to well-intentioned advice. In one great example, Franco's Wiseau either refuses to listen to the suggestions of the first AD (Seth Rogen), or simply has a disconnect between hearing the advice and acting on it, as he proves incapable of filming a take in which his character does not laugh as a reaction to a story about a woman being physically abused by her boyfriend. Exasperated, Rogen's character just gives up so they can move on to the next shot. It's moments of pure and unspoiled cluelessness like this that make The Room sing. Had Wiseau had an ounce more common sense, he would have made a bad movie that no one saw. Instead, he made a bad movie that everyone saw.

Less of what Carrey was doing behind the scenes on the set of Man on the Moon is directly visible on screen. As he terrorized fellow actors (most notably the wrestler Jerry Lawler, playing himself, with whom Kaufman had a real-life mostly fake rivalry), he drove many of them to the brink of quitting the project. You get little bits of the frustration of people like Judd Hirsch and Danny DeVito. You'd have no way of really knowing that by watching the movie, except that it does feel like an uncanny embodiment of Kaufman, and if Carrey had just been switching back and forth between "Jim Carrey" and "Andy Kaufman," who knows if such a transcendent performance would have emerged. There's a telling recollection by Carrey in one of the modern interviews about how Forman felt about it. According to Carrey, Forman called him one night, out of ideas about how to regain control of his actor and bring the production in line. When Carrey threw him a lifeline and volunteered to "fire" both Kaufman and Clifton and then to do impersonations of them, Forman seemed to recognize the value of Carrey's process and rejected the idea. "I don't want it to stop," Forman allegedly told Carrey. "I just wanted to speak to Jim."

In a strange way, director Chris Smith seems to be the link between these two films. Smith, the director of Jim & Andy, was also the director of a documentary classic called American Movie. Like The Disaster Artist, that was also a movie about a Wiseau-like dreamer -- who also happened to have a long mane of black hair -- using his own resources to try to make a film. Mark Borchardt had much more meager and much less mysteriously sourced finances than Wiseau -- he borrowed much of the money from a senile uncle -- but it also cost him a lot less to make his horror short Coven (which I still have not seen, unfortunately). But in his own way he was probably just as delusional as Wiseau ... with, in some respects, an equally happy outcome. The film has turned Borchardt into a cult figure in horror and independent film communities, while Wiseau has eventually turned a profit on the $6 million he spent on The Room, though no one apparently still knows where he got the money to finance the project originally.

I saw The Room four years ago just before leaving Los Angeles, but it's been nearly those 20 years since my viewing of Man on the Moon. I'm curious to watch both again to see if I can see what I now know about these films creeping in from the corners of the frame.

No comments:

Post a Comment