This is the final installment of my 2021 series watching film noir.I finally found the right Humphrey Bogart movies.

That's right, I said "movies." If you thought this was only a 12-movie series, you've got some bonus material coming your way.

If you recall, my guiding principle in launching this series a year ago was to struggle with a chicken-or-the-egg scenario: Was I cool on noir because I don't like Humphrey Bogart, or do I not like Humphrey Bogart because I'm cool no noir?

I started with a Bogart movie (In a Lonely Place) and I always knew I would finish with a Bogart movie. I ended up finishing with three, giving Knowing Noir 14 movies rather than just 12.

If you want to know how I decided to add complication to my schedule in the month of December, a month in which I am also moving to a new house while planning to have no noticeable dropoff in the Christmas I provide my family, well I'll tell you.

I had pretty much decided on one particular Bogart title to finish my noir series, but just to be sure, I decided to go through the other titles that were still sitting in the Letterboxd list I had been adding to all year, just to see what other classic noir I'd be neglecting by not selecting them. I noticed two other titles that also featured Bogart still appearing unwatched in that list. (At least two, but I stopped after two.)

I figured, if I'm trying to decide whether I like Humphrey Bogart or not, let's not let it come down to just one more movie. Let's let it come down to three, and be certain about it one way or the other.

And just so I didn't let the extra ambition swallow me as my month got busier, making me regret I'd decided to add two titles, I front-loaded my three viewings and got them all in the books by December 9th.

Dead Reckoning (1947, John Cromwell)

I finally found the right Bogart movies, but this was not one of them. My first movie of December, on the first of the month, just left me deeper in doubt of its star.

I could tell how little Dead Reckoning was stimulating my engagement with noir by how few notes I took while watching it. Taking notes during a film is tedious and it's something I don't usually do, even though some critics think that helps when you are reviewing a movie. But in this series I've been doing it, since I was specifically trying to notice noir characteristics that I wanted to write about here.

Here is the sum total of what I wrote for this movie:

Bogie's face completely in shadow talking to police

Sexist

Bad singing scene

"The problem with women is that they ask too many questions. They should just spend all their time being beautiful."

She's bad

The "she" there was Lizabeth Scott, Bogart's co-star, who seems intended as a stand-in for Lauren Bacall. I just didn't think her performance was good at all, though it does certainly qualify as a femme fatale. There was something weird about her voice -- was it too deep? not sultry enough? Anyway, ten days later I don't remember. But I just found her off the whole time and I never recovered from it.

The bigger problem, though, was Bogart. I figured out something about Bogart that I guess should not come as a surprise, though it took one of the later films I watched this month for me to reach this conclusion retroactively: If he's not working with a skilled director, he's just not that good. In Dead Reckoning I really noticed how his acting style could best be described as "waiting to say his lines." They say that acting is reacting, but in most of his scenes here, I felt like he was just waiting for the other person to finish speaking so he could spurt out the next bit of his rapid-fire dialogue. (I don't actually know if John Cromwell is considered a good director or not, since I haven't seen any of his other films, but this movie does not provide strong evidence in his favor.)

One convention that has thankfully fallen by the wayside underscored this. It was common in films from that era to see only one half of a phone conversation, and in order not to deaden the pace of the film, the speaker barely pauses for the other person to say anything. The other person is speaking so quickly, and both parties are assimilating what the other person says so instantaneously, that we can hear the whole conversation in about the time it would take just to hear Bogart's half. And that's including him repeating things the other person said so we can understand them. This may not be Bogart's fault, and it may not even be the director's fault, since as I said, it was a convention of films from that era. But taken in combination with the fact that I was already judging Bogart's acting style pretty harshly, it didn't paint a flattering portrait of his skill with the craft.

As you can also see from one of my notes, I really don't like it when Bogart plays a sexist character. Obviously that would be/could be true to life for whatever character he's playing, and I certainly don't hold it against other performers when they play characters who don't respect women. But with Bogart, he's praised for this cool demeanor, dismissive attitudes and quick hard-boiled dialogue, which are part of what made him an icon. I don't dig the role of sexism in completing that picture of the man as a myth and legend.

It occurs to me I haven't told you anything about the plot of Dead Reckoning, and given that I have to write about two other films today, I'm not inclined to start now. Let's just say it involves all the typical double-crosses, paths crossed with unsavory characters, several instances of the protagonist being knocked out and awakening later next to dead bodies. Maybe after 12 months of this I'm just bored of these tropes.

Let's move on.

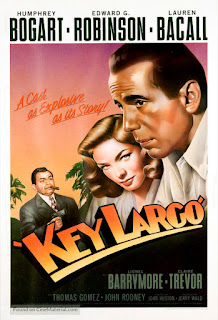

Key Largo (1948, John Huston)

What a difference a week makes.

On December 8th I had this month's second Wednesday date with Humphrey Bogart, and finally, I became smitten.

I took a comparative ream of notes on Key Largo, and as soon as I started watching it, I was sorry it would have to share real estate with two other films in my final Knowing Noir post, because I could talk about this movie all day.

I won't. I'll try to be economic. We'll see how I do.

It was immediately clear what a difference it made for Bogart to be in the hands of a good -- nay, great -- director. John Huston did wonders for Bogart in 1948, and I suppose vice versa, as this was also the year they collaborated on what has always been my favorite Bogart film, Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I think I like Key Largo even better.

The first difference I noticed was technical, as it was immediately clear the thought Huston was putting into camera placements and movements. Huston will zoom in or pan to capture a particularly useful piece of visual information, and one camera setup that seemed simple had a profound effect in terms of just using the available resources to create visual dynamism. There's a moment near the beginning when Bogart's character is pulling in a boat that's moored in a Key Largo harbor, and the camera sits on the boat, getting closer to Bogart and Lauren Bacall with every tug he gives it. As I write this out it does not seem as interesting as it felt in the moment, but it acted as a symbol of how I was in the hands of a man with clear storytelling notions that he knew how to convert into reality.

The other thing I knew I loved about Key Largo, once it became pretty clear what its parameters were, was its choice to take place all in a single location, giving it the contours of a proper frame story. I will tell you about the plot of this particular film, because it's elegantly simple -- and that's something I've determined, over the course of this series, is a boon to any film noir. Bogart plays Frank McCloud, a World War II veteran who travels to the titular locale to visit the widow (Bacall) and father (Lionel Barrymore) of his fellow soldier and friend who died in the war. He's arrived at the Largo Hotel, which they run, at the wrong time for potentially three reasons: 1) It's the offseason, meaning it's incredibly hot and the hotel is not actually open to guests; 2) A hurricane is expected to bear down at any moment; 3) The hotel actually does have a group of ominous looking "guests," who have rented it out for a "fishing trip" -- but really to receive a package delivered from Cuba that will make them a lot of money. In fact, this gang of sketchy guys turns out to be run by the infamous mobster Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson). I suppose there's a fourth reason, which is that police are in the area looking for a couple young Native American men who escaped from prison, who are friends with the widow and her father.

I don't really know the order in which to talk about the things I loved about Key Largo so I will just have at it and see how I go.

I suppose it's best to start with Bogart. It was immediately clear to me how much a director like Huston gets out of this actor. He's specifically not just waiting to say his next line, as you can really see the impact on his face of whatever new piece of information has just crept into his awareness, whether that's a line of dialogue or a shift in the dynamics of a scene (usually inspired by a line of dialogue, I suppose). Key Largo is no less talky than any other noir -- I suppose since it's contained to one location, it might even be more so -- but all the dialogue is to a purpose, clearly advancing the stakes or deepening the portrayals of the characters. I noted that even Rocco's flunkies all had distinct personalities, something the film needn't have done but carries off with a minimum of effort and a maximum of impact. But as you can see I am already getting sidetracked. I started off talking about Bogart.

The full breadth of his charisma is apparent in a role like that of Frank McCloud, where he isn't just lighting up cigarettes and dismissing dames. This is clearly not a sexist character, which is certainly a benefit, but neither is he a purely righteous character either. There's a moment where he reacts to a situation with what appears to be cowardice, and which he writes off as a result of his own self-interest. Later events will prove that this is a bit of bluster and a tendency to be hard on himself, but Key Largo has room for McCloud to be complicated, a man motivated by fear and calculation rather than just the sort of imperviousness to harm that characterizes some of Bogart's shallower performances. You can see Huston taking Bogart and turning him into a human being rather than just a collection of tics and tropes.

Sadly for Bogart, he doesn't get to be the most interesting performer here. That's Edward G. Robinson as Johnny Rocco. What a portrayal. Robinson and screenwriter Richard Brooks (who co-wrote with Huston) depict a gangster whom we can dislike on a human scale, without having to go over the top. In lesser films and probably in newer films, Robinson would have been required to be cruel at every turn, and build up a body count so we can hiss him with more relish. Instead, we get a powerful but extremely intelligent man, one whose ego does motivate him to take certain small reprisals against the people who have insulted him, but who acts out of pragmatism at every turn. Yes he's cruel, and sometimes it's for sport, but what we get here is a man who understands the lay of the land, the advantages and disadvantages he has in any moment, and to what extent a personal insult directed at him should actually impede the larger scheme he has in mind. That doesn't mean there's no room for his character to have linguistic flourishes and moments where he laughs at or withers another character with his comments. It all makes for a dynamic and life-sized portrayal of maliciousness.

It was also really wonderful to see Bacall here, especially so soon after Lizabeth Scott in Dead Reckoning. It's clear what the real deal can do in such direct contrast to a fake. She's comparatively passive as a character, but just her acting -- her reacting, really -- makes it clear how much of a pro she is. There's always something interesting going on on her face, and her sheer charisma is disarming.

Basically I just loved this simple setup that takes place over the course of one afternoon and one evening at this shuttered hotel, with a dozen characters factoring in, also including the gangster's moll, played memorably by Claire Trevor. You'd think there would be a sort of inertness to the film because it doesn't leave the hotel, but nothing could be further from the truth. The narrative just propels things forward and changes the dynamics in forever appealing ways. I think of my favorite film that could be characterized as noir, the Wachowskis' Bound, and how that really all takes place in one apartment. This is just the right setup for me I think.

Three final notes before I will force myself to move on:

1) I love the choice to have this set during the offseason in Key Largo. I expected a film like this to showcase the area at its peak, which probably would have made it feel more ordinary, and also involved multiple locations. It's much better as it is, taking what could have been a travelogue of sorts and turning it into a location that's out of place and time.

2) Some dialogue exchanges that I have to include, just because I loved the writing. I will present them with minimal context in the interest of space and time:

A character's description of a hurricane: "The ocean gets up on its hind legs and walks right across the land."

When a police officer talks about getting hit over the head: "I made a break for the door and the lights went out again."

The mobster who hit him: "I'm the electrician."

"Everybody has their first drink, don't they? But everybody ain't a lush."

"You don't like the storm, do you Rocco? Show it your gun why don't you. If it doesn't stop, shoot it."

"Your head says one thing and your whole life says another. Your head always loses."

3) Although this is clearly film noir, it deviates from it in several important ways. For one, neither Bacall nor Trevor, the only two women in the story, is a femme fatale. It occurs to me that maybe the mere idea of a femme fatale is a problem for me, as it feeds the protagonist's latent sexism, which I've already acknowledged is a problem I have with Bogart. Maybe a solid, not overly complicated story that has a sprinkling of noir elements, but doesn't need to tick all the boxes, is just the type of noir for me.

The Harder They Fall (1956, Mark Robson)

The Harder They Fall (1956, Mark Robson)

It seems fitting to end with what was also Humphrey Bogart's last movie. He died the following year, when all the drinking and smoking led to fatal esophageal cancer.

In truth, you can sort of see that the end was near for him in this film -- not because his performance is limited, but because his skin looks a bit sallow, the wrinkles and bags around his eyes becoming more pronounced. It's hard to know if that's just because he had crossed over into his late fifties, or because the makeup design intended to draw out the way the character has been worn down by life. But I have to think Bogart's cancer would have had something to do with it.

The interesting thing about finishing with this film is that I'm not sure it's actually noir. The Wikipedia entry leads by describing it as a "boxing film noir," which is how I was able to shortlist it for this series, and also a point in favor of its inclusion, as I knew I'd be getting a sort of hybrid film that would provide a nice variation on what I'd been watching. As it turns out, it was so much of a variation that I'm not even sure if noir is a useful label for this movie. Maybe by this point in his career -- its end -- any movie featuring Bogart would get the noir label as long as it was set primarily in cities and there was some sort of criminal element to it.

The Harder They Fall is more of a sports corruption movie, and it's a dandy. The story involves Bogart's Eddie Willis, a character who prompted me to wonder how many times Bogart played a character named Eddie. He's a former journalist who is looking for his nest egg, so he takes a job writing publicity for an up-and-coming boxer from Argentina named Toro Moreno (Mike Lane), the property of corrupt promoter Nick Benko (Rod Steiger). The only thing is, although Toro looks the part, he can neither land nor take a punch. This is no obstacle in the corrupt world of boxing, though -- not when every fighter Moreno fights can be paid to take a dive.

As I was watching this movie a very flattering point of comparison came up in my head. It made me think of my favorite Billy Wilder film, Ace in the Hole, which is also about a journalist who exploits innocents to advance his career. Eddie has a conscience but he's also in it for the wrong reasons, and over the course of the movie, a man who comes on the scene as a joke -- the hulking boxer who is hopelessly untrainable -- really wins our sympathies as a tragic figure, exploited by the machinery of corruption. The great face of this villainy in this film is Steiger, with his absolute disdain for morality, for the hapless boxers who are reluctant necessities for his money-making schemes.

It's a bracingly critical portrait of American sports and American capitalism, though I don't think it's actual noir. There are criminal elements, sure, and there are times when men in fedoras run around in menacing fashion, especially near the end -- almost as though there were an 11th hour attempt to associate The Harder They Fall with noir. Really, though, this is just an exceptional story of greed and the losing battle against it, which takes aim not only at sports but also at journalism. It's also really funny in spots as the satire is on point throughout. Then it can turn on a dime and spend significant energy on brain-damaged boxers who are chewed up and spat out at the other end, left penniless by the huge cuts of their pay taken by the various managers and other skimmers who helped give them a "career."

And I'm glad to report that Bogart is again really good in this film. I don't know Mark Robson's work either, but the performance he gets out of Bogart speaks well of his abilities. This is a sort of perfect swan song for the actor, as he's fighting his own personal battle with selling out and exploitation -- and coming out victorious, I'm glad to say. Not that this was not a typical journey for a Bogart character, but I suppose he could have just as easily ended on a role where he thought "you dames are all alike," and lost that battle.

In the end, the version of Bogart I wanted to like won out in a similar way. Now that I've ended with two films that showed me what I must have always wanted from the actor, I feel a lot better about him on the whole. I just need to find the right movies, and I'm hoping there are some more out there that will give me the feeling that Key Largo and The Harder They Fall have given me.

As an additional note: If I had watched only one movie in December, it would have been Key Largo, so I still would have ended on in this happy place (rather than the Lonely Place where I started off) with Bogart. But I'm glad I fit in the other two, for different reasons -- one I loved, and the other helped me put my finger on the versions of Bogart's screen persona that I don't like.

Because this may be the only good place to squeeze it in, I wanted to tell you that my viewing of The Harder They Fall was part of a Harder They Fall double feature. Knowing that the 2021 Netflix all-Black western directed by Jeymes Samuel was also on my upcoming viewing schedule, I decided to watch both movies called The Harder They Fall in the same evening, which was last Thursday, December 9th. That was about four hours of movie, but I managed to finish it up in the wee hours of the morning. And I really liked the Samuel movie as well, though not as much as Bogart's farewell.

Ordinarily at the conclusion of a series like this, I like to look back and added another couple hundred words recapping the movies I saw and what I ultimately took away from the experience. I kind of still want to do that, but I think I've written enough for today -- and since, as I said before, I still have Christmas shopping and house moving to do, I don't think it's worth it to test your reading stamina any further for now.

But I do hope to officially recap the series in the next couple weeks. Tune back in to see if I manage to fit it in.