But I can watch one pride-themed movie per week this June, and write about it here.

I went cruising for gay-themed movies on my streaming services last night (forgive the cheeky choice of words -- most gay men, known for their sense of humor, would probably approve). Disney+ actually had a good LGBTQI+-themed section they were advertising prominently -- good, as in smartly curated and presented, though not very extensive, as you might expect. (In fact, lest you think I went to Disney first because of the high probability of success in this area, I'll mention I was in there for another reason entirely.) I had already seen all the movies on there, which I actually anticipated might be a problem since I do tend to see a good percentage of the gay-themed movies that break through into the zeitgeist.

I didn't necessarily want the first movie I watched to be something super zeitgeisty -- I was happy to discover something I'd never heard of -- but I also wanted it to have the right look and feel, something of a particular level of craftsmanship. I thought Kanopy would be a good port of call, and they did have a section on "gender and sexuality" -- but it contained mostly cheap-o documentaries, and it wasn't really documentaries I wanted to spend my time on this month.

Finally I ended up on Amazon, which did not have a special section for queer subject matter (shame shame), but I went through the various potentially relevant sections, such as "romance movies," to examine the tags of movies I didn't know. There were a couple prospects that were listed as LGBTQI+ themed, but I'm glad I continued on because the absolutely right option did ultimately present itself.

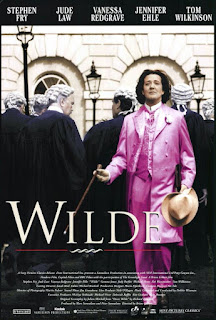

I believe it was in the "historical dramas" or some similar section where I found, without an LGBTQI+ tag, the 1997 film Wilde, directed by Brian Gilbert. (Who, I would later remind myself, directed a film I really liked a few years before this, Tom & Viv, about T.S. Eliot.)

I felt hazily aware of it, but maybe should have remembered it better because Stephen Fry received a Golden Globe nomination for his work in the lead role. Since Oscar Wilde was, of course, gay -- and since I don't actually know all that much about the particulars of his life -- it did indeed feel like the perfect choice.

To say nothing of the cast. The actors I would see as babies in this film included Jude Law, Michael Sheen, Ioan Gruffud, Jennifer Ehle and Orlando Bloom -- the latter of whom was comically listed as a star of the movie in the advertising materials on Amazon, even though he literally only has one scene with literally only one line of dialogue. Then also the likes of Tom Wilkinson and Vanessa Redgrave, not as babies, but as slightly younger adults -- 26 years younger, to be exact. In fact, given the famous faces in this film, the fact that it wasn't more on my radar is a sign of something -- perhaps of the very aversion to homosexual themes this film devotes its time to dramatizing. (Not an aversion on my part, but an aversion on the part of our collective film conversation, which keeps some films in the spotlight beyond the year of their release while relegating others to historical footnotes.)

The film focuses on roughly the final 20 years of Wilde's life, starting in a very strange setting indeed. When I saw the familiar vistas and backdrops of your typical western opening this film, I wondered if perhaps I had wandered into the wrong theater. But it turns out that Wilde had an 1882 visit to Colorado to meet with salt-of-the-earth silver miners on a lecture tour of the U.S. It's here we get a first taste of his proclivities, when he descends into the mine and is greeted by several shirtless men, and makes a comment about their beauty making it more like an ascension to heaven then a descent into hell. Probably confused and not even knowing what a gay person was, the men make nothing of it -- nor was it clear to me to what extent anyone knew Wilde was gay, nor if Wilde even knew it himself, at this point.

He does marry Ehle's Constance, and father two children, but we see him as a bit hesitant to engage in the full extent of the passion she requires in a bedtime kiss. Rather instead, he descends back down to their guest, Robbie Ross (Sheen), who seduces him -- for what appears to be the first time for Wilde, though not for Ross.

Wilde is confused, but he does know that this is what he wants, and he has another fling with Gruffudd's character. (Whose name is John Gray, and who seemed to at least partially inspire Wilde's novel The Picture of Dorian Gray.) It's not until he meets Bosie Douglas (Law), a beautiful but petulant rich kid who bears the title of lord, that he forms a long-term relationship that can't escape public notice -- especially when the boy's father, John Douglas, the Marquess of Queensbury, says he will expose Wilde and have him arrested on charges of indecent behavior if he does not cease and desist with his son. (That's Wilkinson, but that sentence was getting too complicated to mention it.)

Before things go very south for Wilde, we see that there's a chance for the homosexual to win over the homophobe -- the sort of thing we hope can and will occur throughout our society today, to change the tide of hatred toward LGBTQI+ people. (Not that the burden should be on them to change the minds of others, but practically speaking, it is.) Wilde and Bosie are at a lunch when Bosie's father walks in and seats himself at another table, not seeing his son and his son's companion. Bosie has an instinct to flee, but Wilde encourages him not to -- in a preview of what his own choice will be when he is later on trial.

So Bosie goes over to his father and asks him to join them, knowing his father is aware of Wilde's reputation and knowing it will risk exposing him as a "bum boy," which is one of the many epithets his father has at his disposal. This is certainly an act of bravery on Bosie's part, but Bosie frequently acts in cowardice and just plain meanness -- so we can't read too much into it. But he does catch his initially resistant father in a clever trap, saying he doesn't know his father to be a man who places much stock in the opinions of others without forming his own. The elder Douglas cannot argue this and so does join the pair.

We watch as Wilde, using all his renowned gifts for language and persuasion, charms Douglas into a free and easy conversation lubricated by brandy and cigars. He knows just what to say to the man without kissing up to him, honoring his intelligence and speaking eloquently on areas of interest to Douglas, such as horse racing. Eventually they move to philosophy, where Wilde continues to be himself even though he disagrees with Douglas on most matters -- and this is something Douglas notes and respects. In short, just by being his erudite and charming self, Wilde makes himself an excellent companion for lunch, and Douglas talks to him almost as though he's talking to an old friend.

Only moments later we have lost any sense of optimism we may have once had. In Douglas' very next scene, he seems to have forgotten having had this pleasant lunch with Wilde, and doubles down on his objections to the man and his "perversions." It reminds me of how many people in our world today, on how many occasions, find themselves close to embracing the queer person in their life, only to fall back to their previous position of total condemnation. The fact that this moment does not take -- cannot take for someone like Douglas -- ultimately leads to Wilde's downfall.

I can tell you what happens to Wilde, because you can spoil a fiction film but you can't spoil documented history. Wilde serves two years of hard labor when confronted in court with "the love that dare not speak its name" -- more on that in a moment. His sentence is the harshest available to be issued by the disgusted judge. Wilde never cops to sodomy or the other acts of which he is accused, but tries to describe a Platonic ideal of a mentor-mentee love between and older and a younger man, to which he does admit. This is good enough for the court and they slap the cuffs on him. Although Bosie -- who is compromised throughout this movie, frequently treating Wilde terribly, especially in a scene where Wilde is sick in bed -- does try to remain loyal to him, and is there when Wilde is released from prison, a post-script tells us that they parted after three months and Wilde was dead of health problems acquired in prison by 1900 at age 46.

Fry is really excellent in the role, witty and urbane as you would expect, a bon vivant with a bon mot available in any setting. However, I had mistakenly thought of Wilde as someone who was the winner in any social exchange, incapable of losing an argument and haughty in victory. Fry's performance reveals a significant melancholy, and frequently a modesty, to his character. Although he believed philosophically in experiencing everything life has to offer, which leads him to spend time with men in a setting that approximates the late 19th century version of an orgy, he doesn't really seem comfortable with it. In fact, he's a romantic at heart, devoted to Bosie -- even when Bosie frequently is unworthy of his affections.

The phrase "the love that dare not speak its name" made some connections for me to a movie I dearly loved 30 years ago when it came out, but have since been unable to find. (I should probably check again in our new streaming era.) For a long time and perhaps still, the 1994 film A Man of No Importance, starring Albert Finney -- a variation on the title of the Wilde play The Importance of Being Earnest -- was not able to be found for rental, and only for purchase in arcane and incompatible DVD formats. But when I saw it at Portland Maine's arthouse theater my senior year in college, it not only struck me as a warm and sympathetic movie about a man going through very similar trials to what Wilde went through, it also kind of started my relationship with independent/arthouse film, in a very real sense.

In that film, the Irish bus driver played by Finney -- Wilde was also Irish, and he sometimes played up the accent for the purposes of humor -- is mounting a version of Wilde's play Salome. The choice of play is probably enough to make the other townspeople suspicious of his sexual orientation, and indeed, the character talks about "the love that dare not speak its name" as he falls for a younger man in his play, played by Rufus Sewell. His female lead (played by Tara Fitzgerald) is sympathetic to the bus driver but his friends his age ostracize him when they start putting the pieces together, similar to what happened to Wilde in polite society in London. He lives in fear of how Sewell's character will despise him if he discovers the crush.

It's really a shame that to this day, men and women live in fear of what will happen to them if one unenlightened person in their life -- who they love despite their lack of enlightenment -- discovers something about them that will change their relationship entirely. It's no reason to stay in the closet, but it's plenty reason to shake your first at the sky and wish things were different. Maybe one day they will be.

No comments:

Post a Comment