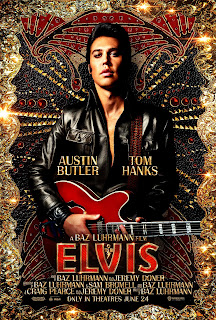

This is the final in my 2023 bi-monthly series rewatching the films of Baz Luhrmann.

We ordered our Christmas cards late this year, but they arrived early. I think it might be part of a ploy by Snapfish to create the impression of excellent customer service, to tell you your order is expected on Friday and then deliver it on Tuesday.

Having been out all day Wednesday at work followed by Ferrari and Saltburn, though, I couldn't start stuffing them in envelopes until Thursday after work, and because of my younger son's school holiday concert, couldn't actually start until that night. When I wanted to watch a movie.

I figured, what better accompaniment to the task than the last entry of Baz Jazz Hands, Baz Luhrmann being a filmmaker whose strengths (some would say weaknesses) come across through an overall impression of what he's doing, not a minute attention to every detail on screen? Especially if you've already seen the movie once?

If I actually wrote in my Christmas cards, it probably wouldn't have worked, but I gave that up ages ago. The only writing I do is the address and the return address on the envelope, and all I was really doing at this stage was writing my return address and the recipient's name on each envelope, kind of like a machine completing a task in parts. I'd look up their addresses later on when I wasn't watching a movie.

Imagine my surprise, then, when the opening scene of Elvis actually features Christmas cards. Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) is putting away a box of Christmas cards on a high shelf when he suffers the stroke that sent him to a hospital bed from which he would never emerge. I almost did a double take, my own Christmas cards right there in my lap.

It's not the only Christmas element in this movie. In fact, there's a whole to do that feels like it takes up 20 minutes about whether Elvis will wear his Christmas sweater and sing "Here Comes Santa Claus" on a television broadcast designed specifically for those two purposes. (Spoiler alert: He does not.)

The salient facts about Parker's death seem mostly accurate -- he died on January 20, 1997, so indeed he could have been putting away Christmas cards, though Wikipedia does not say anything about that. He also did not die until the next morning, so in theory, his deathbed narration of this story, by the light of a night in Vegas, could have also occurred.

That isn't, however, the impression one gets from the Christmas special episode, which bothered me more than it should. But more on that in the moment.

My ranking of Elvis as my #7 film of 2022 was, in part, the thing that inspired me to do this Baz Jazz Hands series. At that time I had seen only two of Luhrmann's six films more than once, and I thought this made a good excuse to revisit the others, to note how Luhrmann's style has developed and solidified over the years. Now that I've done this, I feel I can confidently say he is the only filmmaker -- or for sure, the only filmmaker who has made multiple films -- where I've seen his entire output more than once.

The first 45 minutes of Elvis were an absolute confirmation of the affection I'd felt for it the first time. The colors, the editing, the performance of Austin Butler as the green Elvis, the absolute joy emanating from anything and everything ... it was intoxicating. As Elvis is driving his pink Cadillac, I thought to myself that I had never seen the color pink look quite like that on screen, and I was enthralled by it.

An interesting thing about this film is to watch its color palette become more muted as Elvis sinks deeper into the drug and health problems that would ultimately claim him. You aren't supposed to have as much fun with the second half, or even the final two-thirds, of this film, and that doesn't lessen it as a film -- it just presents the reality of a man's life.

One thing did lessen it, though, and I'd say it probably came about the halfway mark.

I mentioned the whole donnybrook over whether Elvis would meekly accept his commitment of playing a family-friendly Christmas special. In order to draw further thematic resonance from this, Luhrmann chooses to group it together with an event that did not occur, that could not have occurred, at the same time, making it seem as though they were contemporaneous. Two events, actually.

The first in the narrative of these three total events is the assassination of Martin Luther King. We see Elvis receive the news and feel heartbroken.

Not straight away in the narrative, but within maybe ten more minutes of screen time, we start to get into the Christmas special and whether Elvis will behave. Then as they are preparing the Christmas special and there is excessive discussion of Santa Claus coming or not coming to town, and whether he will be reaching town via the lane that bears his name, Robert Kennedy is shot and killed, creating yet more perspective in Elvis regarding what is and what is not important.

Here's the thing: King was shot in April of 1968. Kennedy was shot in June of 1968. There was no Christmas season between those events, or especially at the time of either event.

I said in my review of Elvis (which you can read here if you like) that the movie has a strong sense of emotional truth, if not literal truth at every juncture. I was effectively granting Luhrmann license to take liberties with the truth as long as it was furthering the effective portrait of this man.

However, I do take issue with combining events that were so transparently not related to one another, where it is easily verifiable that they weren't. I first came to this by thinking "Wow, I didn't know Bobby Kennedy was assassinated right around Christmastime." Of course, he wasn't. Luhrmann thought that Elvis' commitment to the Christmas show made an effective metaphor for his selling out of his original persona, a slow-moving compromise that had been going on for some time at this point. And that the death of a political leader he admired would demonstrate just how vacuous were the others things he was doing.

If this were the desire -- and if the movie wants to grapple with Presley's uneasy relationship to Black culture and the debts he owes it -- why not have it be King's death he's struggling with at the same time as the Christmas show? Did Luhrmann just figure people would better remember the time of year King was killed than the time of year Kennedy was killed, so it would make his mild subterfuge less noticeable?

I can't say that this really impacted my enjoyment of the film the second time, but it ate away at me for the rest of the movie, so it obviously stuck in my craw.

Overall, though, this Elvis viewing confirmed the thing I have been steadily realizing all year, or putting into words at least: Luhrmann is a maker of myths. If his characters lack in nuance, it's because he's giving us archetypes, not finely detailed and complicated human beings. If his biopic adheres to the standard components of a biopic, just exploded outward in his unique style, then that's because he wants to make the ultimate biopic, the biopic that might go in the dictionary next to the definition, not something that surprises us by only examining a small part of the subject's life, or examining him by having five different actors play him.

In short, the things Luhrmann does are things I appreciate. The scope of the big screen is strong with this one. He understands that movies are made on a large canvas and that the subject matter should match.

In thinking about filmmakers with a signature style, I think Luhrmann is one as much as Wes Anderson is one. You know you're watching a Luhrmann movie when you're watching it. He comes back to the same sorts of shots, the same sorts of editing techniques, the same anachronistic use of music. There's one shot in Elvis where the casino owner is writing out the terms of Elvis' contract at the International Hotel -- or more specifically, the benefits Parker will get from this commitment -- and I swear there is another shot just like that, focusing ominously on the letters as they are being written, in another Luhrmann film. At this stage I can't remember which one it was. But the moment marked this as a Luhrmann film as much as anything else.

There are differences between a filmmaker like Luhrmann and one like Anderson, though. These differences don't make one better or worse than the other, but I do think they help explain why Anderson gets so much backlash from his haters while Luhrmann gets relatively little, even though he too has plenty of haters.

For one, Luhrmann has made about half the number of films as Anderson in the same period of time. His style has had less opportunity to grate on us for its repetitious nature, especially when he goes nine years between making films, as he did between The Great Gatsby and Elvis.

But I also think the "same style, different subject matter" approach they share befits the sorts of projects Luhrmann tackles better than the sorts of projects Anderson tackles. Again, no slight on Anderson as I really like two-thirds of his movies. But on the ones I don't like, I smack my forehead about how Anderson seems to be going back to the same well, again and again.

With Luhrmann -- especially with the scarcity of movies he gives us -- I feel like this well will never run dry.

Thus concludes the series. I will conclude King Darren before the end of the month, which will make Darren Aronofsky the second director whose every film I have seen more than once, and which will bring all three of my 2023 bi-monthly series to a close.

No comments:

Post a Comment